Working with elderberry, UC Davis students grapple with food systems challenges

This summer, the UCCE Capitol Corridor food systems program partnered with the UC Davis Student Farm to help students understand food processing pathways and value-added food regulations through the lens of blue elderberry. The Student Farm is home to 19 mature elderberry trees, some of which are decades old. The native California shrub provides habitat and forage for a variety of pollinators and animals, and is increasingly used as a hedgerow-based crop on farms. Blue elderberry is also a culturally significant plant for many indigenous people in California. The Student Farm had previously partnered with indigenous community members to harvest elderberry and currently collaborates with campus organization Native Nest to support access to this important plant.

Students and staff spent six weeks harvesting and processing elderberry to understand how it could be shared with the community, regularly drawing upon resources developed by UC SAREP and using the food system program’s Value-Added Profitability Calculator. For more information, read Student Farm intern Taylor Jones’ blog about the six-week elderberry project. A key outcome of the collaboration was a stronger understanding of the food systems assets and challenges in the Sacramento region, including:

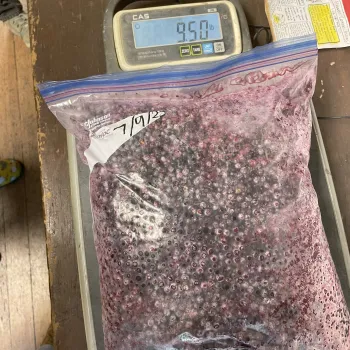

Cold storage: Cold chain management is an important consideration for small farms. Produce needs to be cooled down after harvest, and then maintained at cool temperatures until it reaches the consumer. Of the 110 equipment-only grants awarded as part of the 2024 Resilient Food Systems Infrastructure Program in California, 46 were for some kind of refrigeration including freezer capacity. The Student Farm team ran headlong into this consideration. The plan was to freeze as many berries as possible, then process them into several pilot products when time allowed. But after harvesting a single tree, the students filled one home-scale freezer. The team thought about using freezer space in homes and at a nearby farm, but the lesson was learned: to produce a commercial elderberry product at more than couple of days’ distance from harvest, more freezer capacity would be needed. A 22-cubic-foot chest freezer could cost around $800 new and only accommodate four to five trees’ worth of berries – while the profitability analysis found that the students would need to harvest three times as much to reach a break-even profitability even before accounting for the cost of a freezer. Students wondered if shared cold or frozen storage could increase efficiency across several small farms.

Facility access: The team was interested in a variety of potential value-added elderberry products. With UCCE advisor Olivia Henry, they discussed how products such as dried sachets and syrups could be made – in a home-based cottage kitchen, in a commercial kitchen or with a co-packer. In researching commercial kitchens, the team could only identify one dedicated commercial kitchen in Yolo County. Other value-added producers, as well as food trucks and caterers, typically work with restaurants in Yolo County to access licensed kitchens; a review of Yolo County commissary agreements submitted to the county environmental health department between 2024 and 2025 found that many Yolo-based businesses work with restaurants in Woodland or go to Sacramento for facility access. In researching co-packers or co-manufacturers, the team could only identify one co-packer in the region who may be willing to work with fresh elderberries. All of these facility options added transportation and labor expenses to their profitability calculations.

Commercial-scale equipment: How many elderberries can be dried in a home-scale, nine-tray dehydrator? The team found that a little more than 12 pounds of fresh berries reduced to two pounds of dried berries over a 36-hour period. To dehydrate as much elderberry as would be needed for break-even profitability, the team estimated that someone would need to run the home-scale dehydrator every day for two months. A commercial dehydrator, on the other hand, would offer nine times the capacity. The team discussed the tradeoffs between labor, equipment costs, facility rental fees and co-packer fees. The need for commercial-scale equipment was also reflected in the 2024 Resilient Food Systems Infrastructure Program in California, with awardees receiving equipment such as produce washer/sizers, herb dryers and honey bottling/packaging lines to increase efficiency and unlock market opportunities for small farms.

At the conclusion of the six-week session, the Student Farm team came away with a robust set of data around the farm’s elderberry yield, options for preserving the harvest and possible marketing scenarios. Staff is looking into on-farm field drying of elderberry as an alternative to mechanical dehydration and related facility and equipment costs, with the goal of preserving and donating dried berries to partners across campus and in the community.

Additional reading on adding value to California blue elderberry:

- Buying Blue: Understanding the Market & Assessing Potential for California-grown Elderberry (Engelskirchen & Brodt, 2020)

- Webinar: Understanding Opportunities for Elderberry Sales (2020)