Introduction

While any young person can potentially experience an adverse childhood experience (ACE), not all young people are as likely to be affected by them. Some groups of youth are at a disproportionately high risk. This increased exposure is shaped by systemic factors that are outside of a young person or family’s control. For example, youth who experience marginalized identities, such as youth of color or LGBTQ youth, are more likely to experience ACEs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, n.d.). Similarly, social factors, such as family’s income level, housing insecurity or military status, also increase a youth’s risk of ACEs. Youth with these identities are both more likely to experience ACEs, as well as more experience multiple ACEs.

This increased exposure is not the result of any failings of individual families or cultures, but rather due to complex and overlapping social, economic and political factors. For example, in a low income family, the pressure to provide the necessary resources can cause considerable stress on a parent. This can lead to mental health or substance abuse issues. At the same time, that parent is less likely to have access to mental health resources, potentially exacerbating the parent’s mental health. This can lead to instability in a home and thus ACEs (CDC, n.d.). Or, simply due to the color of their skin, a youth of color is more likely to experience harassment and racism, which is a documented form of ACEs (CDC, n.d.).

Youth who experience multiple marginalized identities, such as queer youth of color or low income youth of color, are at even heightened risk. The unique experience of having multiple marginalized identities, and thus experiencing multiple forms of oppression, is called intersectionality (Crenshaw, 2013).

Groups who may be disproportionately affected by ACEs

Below are some of the groups of youth that are at a disproportionate risk for experiencing ACEs. These groups include (but are not limited to): LGBTQIA+ youth, youth experiencing housing insecurity, youth living in war zones and/or are refugees, youth involved in the juvenile justice system, youth involved in the foster care system, youth in immigrant families and youth in military families. You can read more about these groups below.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual (LGBTQIA+) youth

Youth who identify as LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual) experience trauma at higher rates compared to straight and cisgender youth (i.e. youth whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth) (National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020). LGBTQIA+ youth may experience harassment at school, online bullying, intimate partner violence, abuse (physical, psychological, emotional, and/or sexual), neglect, and other forms of trauma. Youth may experience trauma based on their gender and/or sexual identities. In addition, youth may experience trauma based on other factors, such as cultural identities. The intersections of these identities can prove challenging for youth to navigate.

Youth experiencing housing insecurity

In the U.S., 4.2 million children and youth experience homelessness in the United States (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2023), a disproportionate amount of whom are youth of color and/or LGBTQIA+ youth. Youth who “couchsurf” with friends because they don’t have a home to go back to can experience trauma. Youth whose parents or caretakers experience financial insecurity and cannot afford their mortgage or rent are susceptible to housing insecurity. Youth experiencing homelessness are vulnerable to traumatic experiences.

Youth living in war zones and/or refugees

Youth who are growing up in war or conflict zones experience significant adversity (Ferguson, 2019), including violence, genocide, mass casualty, aid blockades, abductions of children, displacement, food insecurity, lack of medical infrastructure and care, loss of family and friends, destruction of educational infrastructure, among others (Abudayya et al., 2023; Boukari et al., 2024). “Prevalence rates of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were two- to three-fold higher amongst people exposed to armed conflict compared to those who had not been exposed, with women and children being the most vulnerable to the outcome of armed conflicts.” (Carpiniello, 2023 p. 2840). This warzone traumatic stress has significant impacts during and post-conflict on children and women, who are disproportionately impacted and victimized in war and civil violence (Parson, 2000).

Youth who are refugees are also more likely to experience ACEs. As of May 2025, there were over 43.7 million refugees globally, and 40% of them are children (UNHRC). A refugee is someone who has been forced to leave their home due to conflict, persecution or war (Ibid). These youth may experience both the trauma of leaving their home, and are more likely to have experienced either the death of or separation from a parent, as well as discrimination and poverty. In a review of 22 studies, an average of 36% of refugees have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and 18% experience depression (Frounfelker et al., 2020).

Youth involved in the juvenile justice system

In California, there were 5,563 youths residing in juvenile detention, correctional, and/or residential facilities in the year 2017 - a disproportionate number who are youth of color, especially Black youth (Annie Casey Foundation, 2025). Between 75 and 93 percent of youth involved in the juvenile justice system have experienced at least one traumatic event compared to the U.S. national average of 34% of youth (U.S. Department of Justice, 2011). Youth involved in juvenile detention facilities can experience trauma before entering the facility and also after their stay inside the facility (National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020).

Youth in the foster care system

Youth involved in the foster care system can experience trauma, such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research that assessed foster care alumni found that 30% of respondents had PTSD compared with 7.6% of the general population (Pecora et al., 2009). Some examples of trauma may include exposure to someone’s death or an accident, observing a homicide or injury, and/or experiencing an injury or accident (Salazar et al., 2012). A disproportionate number of youth in the foster care system are youth of color and/or LGBTQIA youth.

Youth in immigrant families

Youth in immigrant families are vulnerable to experiencing trauma. Youth from immigrant families may be primary recipients of trauma by having lived experiences of violence, racism, and abuse. Also, youth from immigrant families may have secondary trauma by having a parent(s) and/or caregiver(s) who experience trauma in their community. According to the National Council for Behavioral Health, conditions in detention centers may shape long-term impairments of youth development (National Council for Behavioral Health, 2020).

Youth in military families

In the United States, there are more than 1.6 million military youth (Department of Defense, 2025). Some of these youth have one or two parents who are away from the home because of active duty military service responsibilities. These military youth can experience loneliness and uncertainty as they await their caregivers coming back home from active duty. These youth can experience traumatic events as they navigate their role in relation to war and active duty.

What we can do about this

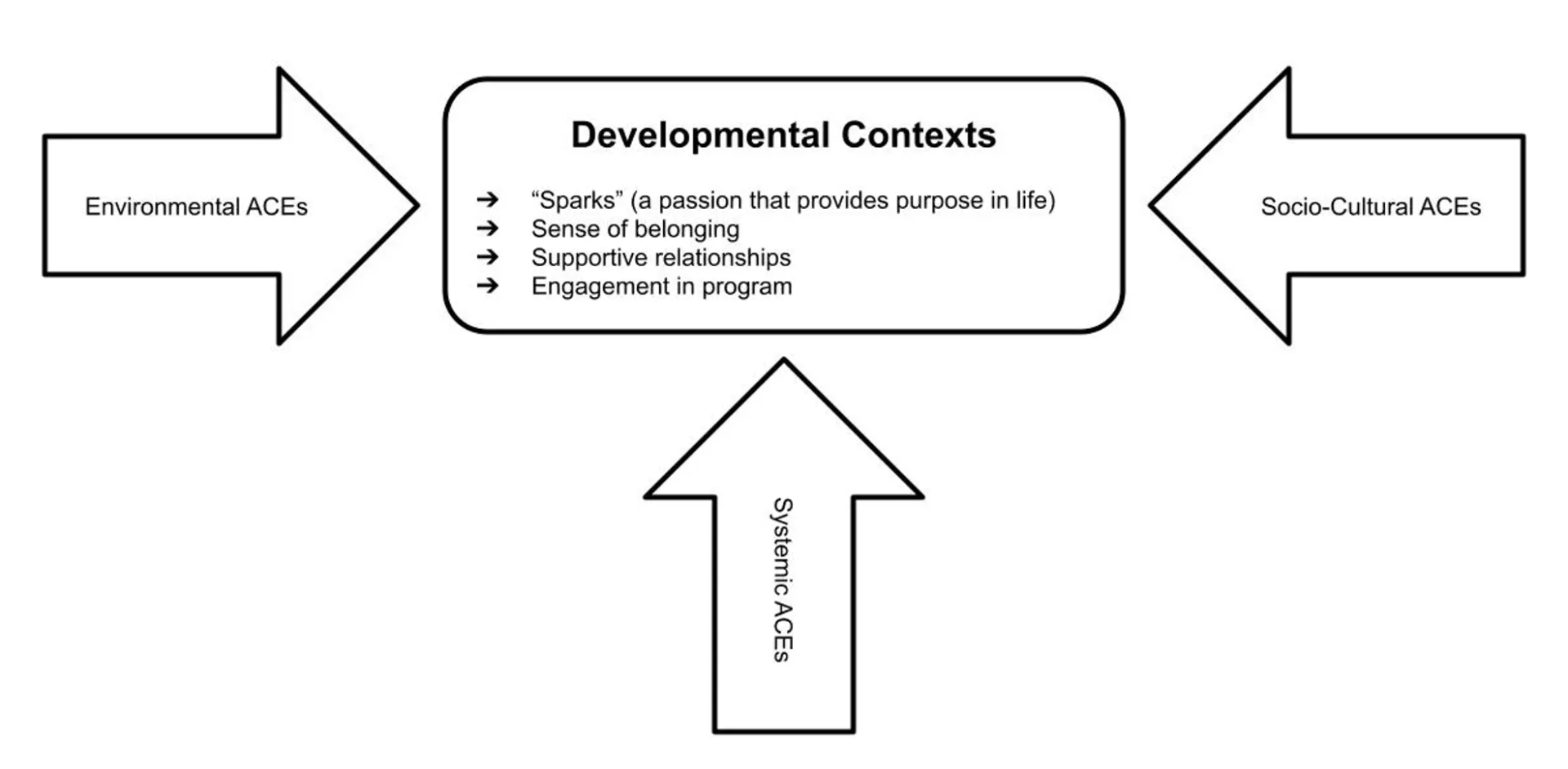

In the 4-H youth development program, we have the opportunity to provide positive environments for our young people who have been exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). In particular, our 4-H national Thrive Model of Positive Youth Development outlines four characteristics of a positive developmental context, which include: 1) “sparks” (i.e. a passion that can help others), 2) a sense of belonging, 3) health relationships, and 4) program engagement. As youth programs foster these developmental context characteristics, youth have the opportunity to thrive.

Figure: Relation between youth developmental contexts and adverse childhood experiences ACEs (Matthew R. Rodriguez, 2025)

When working with youth who have experienced trauma, it’s important for us to provide programs that provide youth with a sense of belonging where they can feel physical, emotional, and psychological safety. In addition, we can support youth who are trying different activities (sparks) and help them see how they can make a positive difference in the lives of others in their community. Also, youth need supportive and positive relationships not just with their peers, but with caring and warm adults. Further, youth who have experienced trauma may need extra help and support to fully engage in youth programming. As we work together, we can certainly “make the best better.”

References

Abudayya, A., Bruaset, G. T. F., Nyhus, H. B., Aburukba, R., & Tofthagen, R. (2023). Consequences of war-related traumatic stress among Palestinian young people in the Gaza Strip: A scoping review. Mental Health & Prevention, 32, 200305.

Boukari, Y., Kadir, A., Waterston, T., Jarrett, P., Harkensee, C., Dexter, E., ... & Devakumar, D. (2024). Gaza, armed conflict and child health. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 8(1), e002407.

Carpiniello, B. (2023). The mental health costs of armed conflicts—a review of systematic reviews conducted on refugees, asylum-seekers and people living in war zones. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(4), 2840.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES): Risk and Protective Factors. Retrieved May 8, 2025 from https://www.cdc.gov/aces/risk-factors/index.html.

Crenshaw, K. W. (2013). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In The public nature of private violence (pp. 93-118). Routledge.

Ferguson, J. (2019). ACEs in Conflict and Post-Conflict.

Frounfelker, R. L., Miconi, D., Farrar, J., Brooks, M. A., Rousseau, C., & Betancourt, T. S. (2020). Mental health of refugee children and youth: Epidemiology, interventions, and future directions. Annual Review of Public Health, 41(1), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094230

National Council for Behavioral Health. (2020). Mental Health First Aid USA Youth Manual (Version 2.0, p. 39).

Parson, E. R. (2000). Understanding children with war-zone traumatic stress exposed to the world's violent environments. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 30(4), 325-340.

Pecora PJ, White CR, Jackson LJ, Wiggins T. Mental health of current and former recipients of foster care: A review of recent studies in the USA. Child & Family Social Work. 2009;14(2):132–146.

Salazar AM, Keller TE, Gowen LK, Courtney ME. Trauma exposure and PTSD among older adolescents in foster care. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology. 2013 Apr;48(4):545-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0563-0.

UNHCR(n.d.). What is a refugee? UNHCR. Retrieved May 8, 2025, from https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/what-is-a-refugee/