Table Olive Yields Benefit from a New Approach to the Age-old Practice of Pruning

Elizabeth Fichtner, UCCE Farm Advisor, Tulare and Kings Counties, and

Carol J. Lovatt, Professor of Plant Physiology, Emeritus, Dept. of Botany and Plant Sciences, UC Riverside

Pruning is essential for sustaining orchard productivity, especially the yield of commercially valuable size (CVS) fruit. The main value of pruning is to open the canopy for light penetration—No light, no flowers, no fruit! Additionally, pruning allows for management of tree height and maintenance of space between trees and drive rows, thus facilitating harvest and pest control activities as well as promoting the rejuvenation of older trees. Last, pruning to raise tree skirts may allow cold air to drain through the orchard and ensure that sprinklers are not wetting the low hanging fruit, which may promote disease.

Pruning is also a well-known crop reduction tool for mitigating the negative effects of a heavy ON crop when alternate bearing (AB) occurs. Olive trees are prone to AB, production of a heavy ON crop one year followed by a light OFF crop the next. The ON crop is characterized by large yields with small size fruit that have reduced commercial value and typically mature late. Conversely, the OFF crop consists of large size fruit due to the low yield, which may not be cost effective to harvest. AB adversely affects the consistency of the fruit supply, thus having a negative economic impact on every step within the production chain from farm to consumer. Use of plant growth regulator sprays of naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) or pruning to reduce crop load during the ON year have shown promise in evening out olive production from year to year. However, implementation of these strategies for optimal results has remained elusive. We previously reported that “Olive Yields Benefit from a New Strategy Using Naphthaleneacetic Acid to Manage Crop Load” in the November/December, 2024, issue of Progressive Crop Consultant. Here we report the results of field research sponsored by the California Olive Committee to answer the questions of when, how much and how frequently to prune ‘Manzanillo’ table olive trees to reduce alternate bearing and generate better cumulative annual yields of commercially-valuable size (CVS) fruit.

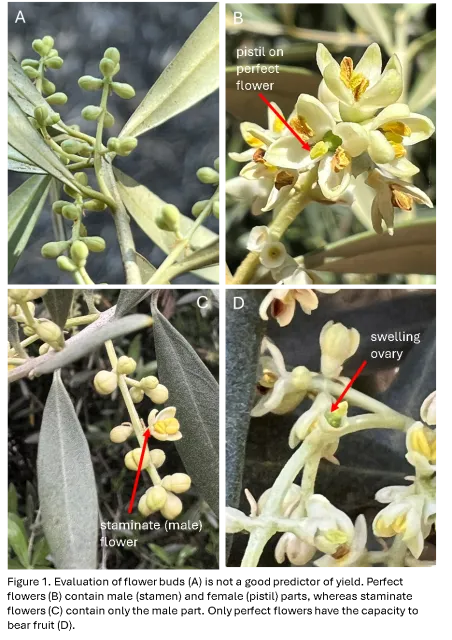

WHEN? Pruning of tree crops is typically carried out in the winter when orchard management requirements are minimal and trees are more or less dormant, resulting in minimal vegetative regrowth. However, pruning at this time is compromised by the ack of knowledge as to whether the upcoming spring bloom and fruit set will be ON or OFF. Delaying pruning operations until bloom allows growers to evaluate the current season’s yield potential and adjust pruning intensity accordingly. Further delay of pruning until after bloom enables growers to evaluate fruit set before reducing crop production on pruned sections of the tree. Because over 98% of olive flowers do not set fruit, assessing the abundance of flower buds alone (Figure 1A) is not a good predictor of yield in some years. Olives have two types of flowers, perfect flowers containing both female (pistil) and male (stamen) flower parts (Figure 1B), and staminate flowers (Figure 1C) containing only male flower parts. The ratio of perfect flowers to male flowers is determined several weeks prior to bloom when environmental stresses induce a fraction of the pistils to abscise. Note that the base of the pistil, is the ovary, which develops into an olive fruit. Thus, only perfect flowers have the potential to bear fruit. Fruit set is also influenced by climatic conditions at bloom. For example, heat during bloom in ‘Manzanillo’ orchards limits pollen development, resulting in reduced fertility. In seasons characterized by heat during bloom, shotberries (Figure 2A) (parthenocarpic fruit; i.e, fruit forming without syngamy and thus, without a seed, which never fully develop) may be prevalent in ‘Manzanillo’ table olive orchards.

To mitigate the impact of the current ON crop on the successive year’s crop, fruit removal should be completed before pit hardening, a phenological stage that occurs in July. After pit hardening, the current season’s crop suppresses summer vegetative shoot growth (both the length and number of shoots that develop). This limits the number of nodes (points of leaf attachment) available for floral bud development for next spring’s bloom. Conversely, pruning cannot be delayed too late into the summer. Pruning stimulates the tree’s production of gibberellins, plant growth regulators that may inhibit the transition of vegetative buds to floral buds, a developmental event that is initiated in late-August through mid-September. Pruning approximately 28 days after full bloom (i.e. early June) (Figure 2B) prevents the suppression of in-season vegetative shoot growth caused by the ON crop and allows sufficient time for dissipation of gibberellins prior to the transition to floral buds.

HOW MUCH? Pruning both sides of the tree and topping during an ON-crop year makes sense only if selective pruning is done to balance floral and vegetative shoots to sustain the yield of commercially valuable size fruit. For table olive, evidence suggests that mechanical pruning on two sides of the tree, especially with topping, in a single year might be too severe, converting ON-crop trees into OFF-crop trees and the ON year into an OFF year, which turns the following year into an ON year. An alternate approach with less impact on yield is to prune only one side of an ON-crop tree to generate ON- (unpruned) and OFF- (pruned) sides of trees (Figure 3), allowing for mitigation of alternate bearing at the tree and orchard level.

HOW FREQUENTLY? To address this question, field research was conducted with ‘Manzanillo’ olive trees to evaluate the influence of pruning 28 days after full bloom to one side of the ON-crop tree and then the other, either annually (side 1 in year 1 and side 2 in year 2) or biennially (side 1 in year 2 and side 2 in year 3), on total yield, yield of CVS fruit and the severity of AB over two ON/OFF cycles (4 years). For each 2-year ON/OFF cycle, ABI was calculated for total yield and yield of CVS fruit: ABI = (year 1 yield – year 2 yield)/(year 1 yield + year 2 yield), in which yield is kilograms of fruit per tree and the difference in yield between years 1 and 2 is expressed as an absolute value.

Starting with an ON-crop year, severity of AB for the ON-crop control trees in this research, based on alternate bearing index (ABI), where 0 equals no AB and 1 is complete AB (crop one year, no crop the next), was 0.94 for total yield. Pruning one side of the tree and then the other side annually reduced ABI 24% to 0.72, whereas pruning one side of the tree and then the other biennially reduced the ABI 50% to 0.47. There was no significant difference in 4-year cumulative total yield across treatments. Taken together, the results indicate that for each year of the 4-year period, total yields of trees pruned biennially were more uniform than trees pruned annually or not at all. More uniform annual total yields improve the economics of all steps in the supply chain from farm to consumer.

Yield of CVS fruit was determined only for the last three years of the experiment. Annual pruning of one side of the tree and then the other increased 3-year cumulative yield of CVS fruit by 58% (a net increase of 25 kg/tree) and reduced ABI by 24% (ABI = 0.61) compared to the untreated ON-crop control trees (ABI = 0.80). In contrast, biennially pruning one side of the tree and then the other resulted in 2.7 times more CVS fruit (a net increase of 73 kg/tree/3 years) and reduced ABI 54% (ABI = 0.37) compared to the ON-crop control trees over the same 3-year period. The increased and more uniform annual yields of CVS size fruit obtained with biennial pruning provides growers with greater, more reliable annual revenues. The results demonstrate the value of a year-long rest period between pruning events for achieving better economic returns in table olive orchards. We previously reported that the year of rest between biennial applications of NAA to one side of ‘Manzanillo’ olive trees and then the other also increased yield of CVS fruit and reduced ABI compared to annual NAA treatment (Olive Yields Benefit from a New Strategy Using Naphthaleneacetic Acid to Manage Crop Load, Progressive Crop Consultant, November/December, 2024).

Optimizing the pruning approach taken to manage crop load has significant potential for mitigating alternate bearing in table olive orchards and increasing yield of CVS fruit and grower income. Pruning 28 days after full bloom allows for fruit removal before suppression of the following year’s crop and gives growers an opportunity to evaluate fruit set prior to making cuts that will limit the current year’s production. The year without pruning reduces the cost of the biennial pruning strategy by 50% compared to annual pruning. To further reduce pruning costs, growers could opt to prune one side of the trees on either side of a drive row and then skip the next drive row to leave the other side of two rows of trees unpruned. This technique would facilitate orchard access in unpruned rows until woody debris is mowed and might reduce the costs of mowing by limiting the area serviced by the mower.

Results of this research demonstrate the potential horticultural and economic value of this new approach to pruning table olive trees at 28 days after full bloom on one side of the tree and then the other biennially for evening out crop load to reduce AB across years and improving cumulative yield of CVS fruit over multiple years. The improved efficacy of pruning (or applying NAA) biennially is currently being tested for reliability in a second experiment in a new commercial orchard.

Figure Legends

Figure 1. Evaluation of flower buds (A) is not a good predictor of yield. Perfect flowers (B) contain male (stamen) and female (pistil) parts, whereas staminate flowers (C) contain only the male part. Only perfect flowers have the capacity to bear fruit (D).

Figure 2. Parthenocarpic fruit (A) called shotberries are common in ‘Manzanillo’ olive in years characterized by heat or cold wet weather at bloom. Pruning 28 days after full bloom (B) allows growers to evaluate fruit set before making pruning cuts that may limit returns in the current season.

Figure 3. Eliminating crop on one side of the tree (A) allows for production of the crop on the alternate side of the tree (B). When carried out biennially, the result is more uniform total yields, increased yields of CVS fruit and reduced alternate bearing.